Is Alzheimer’s Disease Type 3 Diabetes?

Unraveling the link between glucose metabolism and brain health

A recent longitudinal study examined how glucose levels in early adulthood impact the risk of developing Alzheimer’s later in life.

Data from nearly 5000 participants (35–50 years old) over the course of 38 years were analyzed to determine correlations between metabolic markers and Alzheimer’s disease.

Individuals with higher blood glucose levels during middle adulthood had a 14.5% higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease later in life. But why might we observe this association between impaired glucose metabolism and deterioration of brain function?

How Can Defects in Glucose Metabolism Impair Brain Function?

The brain uses glucose as its primary energy source but can also use ketones under fasting conditions. High blood sugar coincides with a reduced ability to uptake glucose into the brain, making diabetes and obesity major risk factors for dementia.

ApoE4 is a gene that is strongly associated with an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s later in life. Having one mutated copy doubles your risk, and having two mutated copies increases risk 10-fold.

Young adults who carry one copy of the implicated ApoE4 variant have abnormally low levels of glucose in regions of the brain that are affected by Alzheimer’s disease — namely the posterior cingulate, parietal, temporal, and prefrontal cortex.

How Do Our Bodies Regulate Insulin Secretion?

Evidence for insulin resistance in the brain is where Alzheimer’s disease sometimes gets its moniker of “type 3 diabetes.” A paper published last year by researchers in Japan offers yet another piece to the puzzle. Amyloid beta (Aβ), a protein often implicated in neurodegeneration, may play a role in regulating insulin secretion.

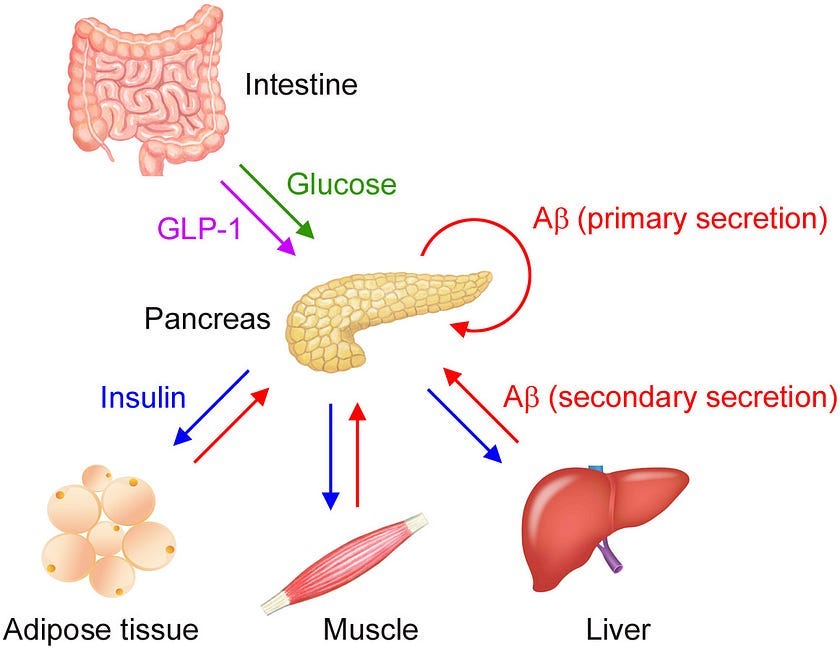

While plasma Aβ levels are traditionally thought to reflect brain pathology, the researchers demonstrated that glucose- and insulin-sensitive tissues like the pancreas, adipose tissue, skeletal muscles, and liver also secrete Aβ, which in turn inhibits insulin secretion by β-cells in the pancreas.

As our blood glucose levels rise after a meal, the pancreas secretes insulin, which stimulates glucose uptake by insulin sensitive tissues, thereby decreasing blood glucose. But there’s more to the story: the pancreas also secretes Aβ when stimulated by glucose.

Researchers refer to this glucose-dependent secretion of Aβ as “primary secretion.” Insulin circulates and binds to peripheral target tissues, triggering muscle, liver, and fat tissue to then secrete Aβ in an insulin-mediated manner, what the researchers call “secondary secretion.”

While glucose is the main driver of insulin secretion, plasma Aβ may help fine tune it. Aβ secreted from islet β-cells in the pancreas adjusts insulin secretion in an autocrine manner and Aβ secreted from insulin-targeted organs suppresses insulin secretion in an endocrine manner. This two-step regulation of insulin helps keep blood sugar levels stable.

Aβ secreted from peripheral tissues likely functions as an organokine, an endocrine factor that is involved in crosstalk between organ systems and contributes to glucose and insulin homeostasis. In response to insulin, muscle, liver, and fat tissue release their own organokines, known as myokines, hepatokines, and adipokines, respectively.

Over ten years ago, another research group identified APP as a top candidate gene that regulates insulin secretion from pancreatic islets and reported that loss of APP in mice leads to increased insulin secretion from islets in response to glucose, but the mechanism for why this occurred was previously unknown.

We now know that APP knockout mice exhibit upregulated insulin secretion because APP-derived Aβ negatively regulates insulin secretion. This relationship suggests a connection between Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes. A couple other mechanisms might also explain the connection:

How Does Amyloid Beta Build Up in the Brain?

In the body, Aβ can be found in the brain and in plasma. In order to be transported into circulation, Aβ in the brain must cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) through a receptor known as low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1).

Transport of Aβ from circulation into the brain is mediated by the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE). High blood glucose and insulin levels, or hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia, can cause prolonged production of Aβ in plasma, which can negatively alter the equilibrium between brain Aβ and peripheral Aβ by suppressing Aβ efflux from the brain.

In other words, chronically elevated Aβ levels in circulation may impair transport of Aβ out of the brain. At the same time, high levels of circulating insulin can cross the blood-brain barrier and prevent the breakdown of Aβ in the brain by competing for insulin-degrading enzyme.

As a result, Aβ becomes abundant in the brain because of reduced excretion into the circulation and insufficient enzymatic degradation. The enriched Aβ may start to clump together into soluble oligomers, triggering cognitive dysfunction and the resulting cascade of events that leads to Alzheimer’s disease.

The authors also note that plasma Aβ levels can be used as a diagnostic biomarker of AD but only in the fasting state since plasma Aβ levels change rapidly with food intake.

How Are Diabetes & Alzheimer’s Disease Connected?

However, several previous studies have observed different results. In humans, diabetes is associated with cerebrovascular lesions, neurodegeneration, and cognitive dysfunction, but not brain amyloid accumulation, as measured by amyloid PET imaging. But it’s important to note that soluble Aβ oligomers can’t be visualized using amyloid PET.

Similarly, a mouse model of Alzheimer’s and diabetes demonstrated accelerated cerebrovascular amyloid deposition and worsening cognitive dysfunction without an increase in brain Aβ levels, so different pathways may be at play.

One alternative theory is that diabetes-induced Aβ transport into the brain encourages amyloid deposition at the vascular wall, damaging the ability of the glymphatic system, responsible for housekeeping and waste clearance, to discharge brain Aβ into circulation.

Diabetes may affect brain Aβ levels differently depending on disease status with enhanced Aβ deposition near blood vessels observed early on and brain tissue damage observed later. More research is needed to determine whether brain Aβ levels increase in diabetes.

For now, what we can say is that maintaining healthy insulin sensitivity may substantially reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s disease later in life.

This is so interesting, Nita! So does this mean we can prevent Alzheimer’s by exercising and eating less sugar? (Or maybe eating MORE sugar, that would be fun)

I wonder what role statins play in the development of insulin resistance. Reports indicate that 10% of statin users develop type 2 diabetes, independent of other factors. Do you have any thoughts on that, Nita? This was a wonderful article again. Thank you.