Why Gene Editing Can't Fix Everything

Benefits of genetic diversity, deleterious on-target effects, and a call to proceed with caution

Seven years ago, the world’s first genetically edited babies were born, twin girls given the pseudonyms Lulu and Nana; Chinese scientist He Jiankui had used CRIPSR technology to edit the CCR5 gene in human embryos with the aim of conferring resistance to HIV. But before we start reinventing ourselves and mapping out our genetic futures, we might take a moment to reevaluate the risk profile of gene editing.

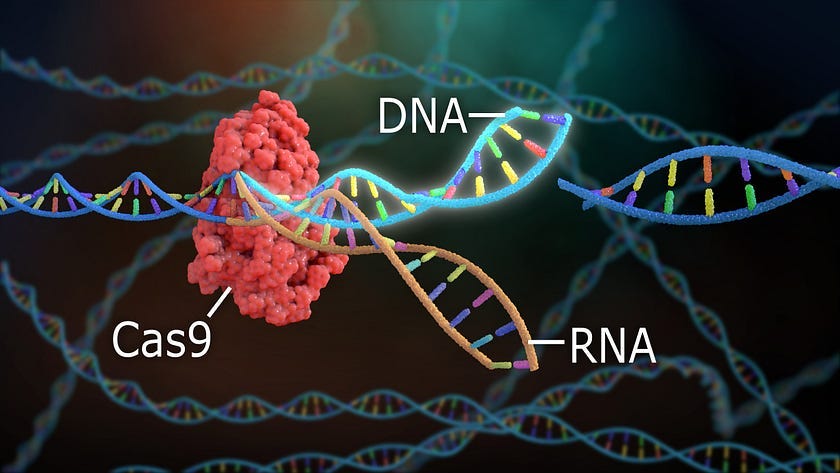

CRISPR-Cas9 borrows a concept from bacterial immunity to edit human genes.

CRISPR-Cas9 takes advantage of the bacterial equivalent of adaptive immunity. CRISPR, which stands for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, is an RNA mediated bacterial defense against viral or plasmid DNA.

When a bacterium is exposed to a pathogen such as a bacteriophage, it stores some viral DNA in its own genome in “spacers,” which serve as excerpts from sequences of past enemies that have attacked the bacterium or its ancestors.

The spacers essentially function as genetic mug shots, allowing the bacterium to remember pathogens in case of future invasions. When required, the CRISPR defense system will slice up any DNA matching these genetic fingerprints.

In 2012, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier demonstrated how CRISPR could be used to slice any DNA sequence of choice. The CRISPR-Cas9 system allows researchers to not only recognize and remove DNA sequences but also modify them.

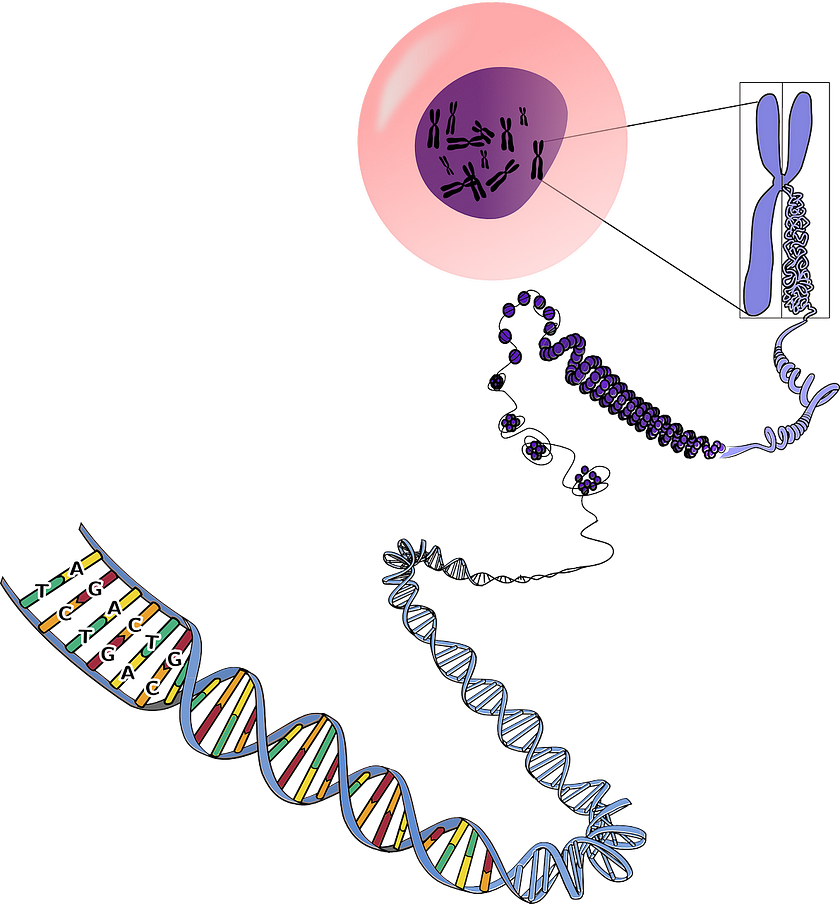

The completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003 provided a copy of the genetic book of life; CRISPR offers a way to erase and “correct” certain words in that book. Treating blood disorders, such as sickle cell anemia, which is caused by a single point mutation, could be possible.

Of course, this newfound power raises several ethical concerns. The major worry among scientists revolves around the long-term consequences of germline modification, meaning genetic changes made in a human egg, sperm, or embryo.

Edits made in the germline will affect every cell in an organism and will also be passed on to any offspring. If a mistake is made in the process and a new disease inadvertently introduced, these changes will persist for generations to come. Germline edits are essentially forever.

Human germline modification can also open the door to designer babies, allowing not only for the cure of genetic diseases but also the installation of genes to offer protection against infection, Alzheimer’s, and even aging.

For many, the thought of controlling our own genetic destinies seems to be a very slippery slope, conjuring up dystopian images of Frankenstein or Brave New World. In 2015, Doudna and other scientists proposed a moratorium on the use of CRISPR-Cas9 for human genome editing until safety and efficacy issues could be more thoroughly addressed.

CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing technology may have unintended consequences.

CRISPR is currently being used in clinical trials for cancers and blood disorders; since these interventions won’t lead to heritable DNA changes, these trials don’t face the same ethical dilemmas as Dr. He’s experiment but may nevertheless carry risks.

Doubts persist about the safety and efficacy of the CRISPR gene editing system, as many other initially promising technologies have failed. Conventional gene therapies, which attempt to insert healthy copies of genes into cells using viruses, faced many early setbacks, including the tragic death of 18-year-old Jesse Gelsinger in 1999 during a gene therapy trial for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency.

While more precise than traditional gene therapy, CRISPR nonetheless sometimes results in unintended edits. But even precise cuts can have unexpected consequences.

Two separate 2018 studies published in Nature Medicine, one conducted by the Karolinska Institute in Sweden and the other by Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research, concluded that CRISPR edits might increase the risk of cancer via inhibition of a tumor suppressor gene called P53, which has been described as “the guardian of the genome” due to its crucial role in maintaining genomic stability.

Double-stranded DNA breaks made by CRISPR activate repair mechanisms encoded by P53 that instruct the cell to either mend the damage or self-destruct. Making these types of edits successfully would therefore require inhibition of P53; however, cells could become more vulnerable the development of cancer as a result.

CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing can also trigger a phenomenon called chromothripsis, a catastrophic event where a chromosome shatters and reassembles incorrectly. A 2021 study published in Nature Genetics found that CRISPR-Cas9 editing can cause extensive chromosomal rearrangements, including large deletions and complex genomic alterations at the target site.

These on-target consequences occur when the DNA repair machinery attempts to fix the Cas9-induced break but does so imprecisely, leading to the loss of tumor suppressor genes or activation of oncogenes.

“We don’t always fully understand the changes we’re making,” says Alan Regenberg, a bioethicist at Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics. “Even if we do make the changes we want to make, there’s still question about whether it will do what we want and not do things we don’t want.”

But even if genetic editing technology like CRISPR-Cas9 could be made sufficiently accurate and precise, the idea that certain genes can be categorized as either advantageous or deleterious is fundamentally flawed.

Genetic strength or weakness is relative, as perceived imperfections may actually confer resilience in a changing environment.

It is an error to imagine that evolution signifies a constant tendency to increased perfection. That process undoubtedly involves a constant remodeling of the organism in adaptation to new conditions; but it depends on the nature of those conditions whether the direction of the modifications effected shall be upward or downward. Retrogressive is as practicable as progressive metamorphosis.

— English Biologist Thomas Henry Huxley, 1888

In biology, those organisms that are most suited to their environment exhibit the highest fitness, a measure that accounts for both survival and reproduction. The accumulation of mutations over time is thought to contribute to many disease processes, but genetic diversity can also be beneficial for an organism when faced with a changing environment or unanticipated stress, such as drought or illness.

Discussions on rigid natural selection should give way to more nuanced conversations on “balancing selection, the evolutionary process that favors genetic diversification rather than the fixation of a single ‘best’ variant,” as described by Professor Maynard V. Olson at the University of Washington.

Evolution has allowed many potentially deleterious genes to remain in the gene pool due to their ability to impart a selective advantage to individuals with carrier status, a phenomenon referred to as heterozygote advantage.

Sickle cell anemia is a disease inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern — two copies of the problematic gene variant are necessary for disease expression. However, having just one copy of that variant confers resistance to malaria, which may explain the increased prevalence of sickle cell anemia in areas where malaria is more common, namely India and many countries in Africa.

In other words, malaria acts as a selective evolutionary pressure maintaining the occurrence of the sickle cell variant in the gene pool.

To further examine the utility of genetic diversity, consider the fact that over half of all hepatocytes (liver cells) in humans exhibit polyploidy, meaning that instead of having two copies of each chromosome, they have four, eight, or even 16.

Cells that contain an abnormal copy number of chromosomes are often seen as aberrant, but considering the liver’s role as a waste-processing plant, this type of built-in redundancy likely comes in handy upon exposure to DNA-denaturing substances. If a toxic substance damages a gene on one chromosome in a liver cell, the backup copies of that chromosome can ensure the gene will still function properly.

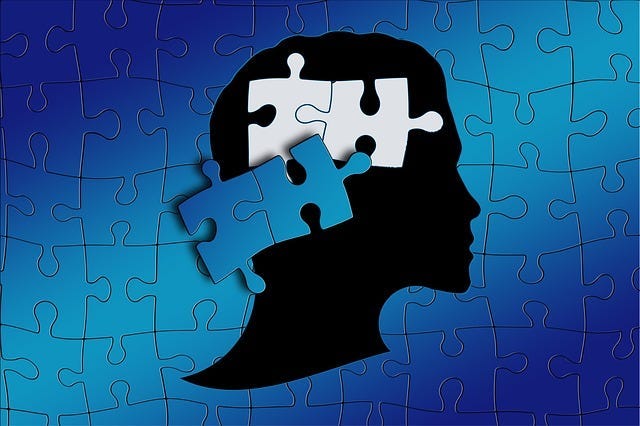

Harvard geneticist George Church offers some anecdotal evidence supporting the maintenance of neurodiversity in the gene pool, explaining that people with autism have historically been described as intellectually disabled. But very often, if they can become high-functioning, they’re the opposite. They actually contribute things to society that nobody else sees. Church himself has narcolepsy and struggled with dyslexia as a child, differences that he feels have contributed to his creative abilities.

The Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity says dyslexia affects 20 percent of the U.S. population and accounts for 80–90 percent of all individuals with learning disabilities. A study conducted by London’s Cass Business School found that dyslexia is much more common in entrepreneurs than in the general population, as 35 percent of U.S. entrepreneurs that were studied exhibited dyslexic traits. Researchers also determined that compensatory strategies, such as ability to delegate and enhanced oral communication skills, likely contributed to success in the business arena.

Shark Tank investor Barbara Corcoran credits dyslexia for helping her develop empathy and making her “more creative, more social and more competitive.” Similarly, Richard Branson, Charles Schwab, and Ikea founder Ingvar Kamprad have spoken about how dyslexia fostered innovation and helped shape their unique worldviews. Considering the countless advantages of a perceived disability, any ill-conceived efforts to normalize the genetic bell curve could mean missing out on the incredible potential of genetic neurodiversity.

Speculation surrounding “designer babies” is based more in science fiction than scientific fact.

Man is a maker and a selector and a designer, and the more rationally contrived and deliberate anything is, the more human it is.

— Joseph Fletcher, one of the founders of bioethics, 1971

Basic research on gene editing and the use of somatic gene editing to heal individuals who are sick are generally widely accepted among the public. The waters become murkier when we consider germline editing and the possibility of preventing disease or altering traits unrelated to health needs.

In the 1970s, scientists first began to establish distinctions between somatic and germline genome modifications; somatic edits only affect a single individual while germline edits can be passed down over generations.

By the mid-1980s, bioethicists began to argue that the morally relevant line was between disease and enhancement rather than somatic and germline. Discussions of heritable enhancements in particular raise fears of a possible return to eugenics.

Designer babies is a term commonly used in the vernacular to refer to babies with genetic enhancements. John Fletcher, former head of bioethics at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), once wrote,

The most relevant moral distinction is between uses that may relieve real suffering and those that alter characteristics that have little or nothing to do with disease.

Many scientists today share the sentiment that treatment and prevention of “disease” constitute acceptable uses of CRISPR technologies while “enhancement” applications should be discouraged, but the boundary between the two is riddled with semantic discord.

Pharmaceutical companies frequently invent new medical diseases in a process known as medicalization. Neither can the medical profession be relied upon to make the distinction, as many plastic surgery practitioners conduct procedures that can more aptly be described as enhancement. Moreover, the line delineating disability and disease is often blurred, and many perceived shortcomings may in fact represent normal variation on the phenotypic spectrum.

The discussion of whether we can or should modify human characteristics may be a moot point since our knowledge of which genes affect complex traits such as height, intelligence, and eye color is still limited. Additionally, most traits are influenced not only by genetics but also environmental factors, and monozygotic twin studies demonstrate that genes alone cannot predict whether physical traits will be expressed.

Furthermore, genes that encode for physical traits may also impart increased vulnerability to certain diseases. For example, variations in the MC1R gene responsible for red hair color may also increase the risk of developing skin cancer.

The efforts of Dr. He Jiankui to confer HIV resistance to twins Lulu and Nana may have also resulted in increased susceptibility to infection by West Nile virus or influenza. As always, trade-offs exist, and the idea of the “perfect specimen” is a fallacy. Any efforts to gain genetic advantages will always be subject to the limitations of biology.

Our understanding of gene-disease links is based on limited data and is therefore incomplete. The singular “wild-type” does not exist.

How do we define a mutation? The simple answer is a genetic sequence that differs from the agreed-upon consensus or “wild-type” sequence. After the completion of the Human Genome Project in 2003, the arduous process of genome annotation began. Genome-wide association studies, or GWAS, began examining population data over time to look for possible associations between genetic variants, or genotypes, and physical traits and diseases, or phenotypes.

Unfortunately, these studies often fail to employ random sampling, and 96 percent of subjects included in GWAS have been people of European descent. In fact, scientific disciplines frequently disproportionately sample from WEIRD (western, education, industrialized, rich, democratic) populations, whether studying genetic diseases or human gut microbiota.

Given the sources of genetic information used to determine “wild-type” sequences, we may be using information that is relevant to one demographic but not another. According to Maynard Olson, one of the founders of the Human Genome Project, the wild-type human simply doesn’t exist, and

genetics is unlikely to revolutionize medicine until we develop a better understanding of normal phenotypic variation.

These words seem to have fallen on deaf ears, however, as evidenced by the burgeoning numbers of genome-wide association studies conducted over the last 12 years. Most of the associations discovered thus far are only correlative, and few studies have been conducted to determine whether observed associations are indeed causal.

But the majority of afflictions commonly affecting the general population, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, Alzheimer’s, and Parkinson’s are not caused solely by mutations.

Disease seldom arises as the result of genetic mutation alone.

The critical take-home medicine here — one that needs to be reinforced over and over — is that as we enter the age of genomic medicine, simply having a mutation in a disease gene does not mean you have the disease or will get the disease.

— Harvard geneticist Robert Green, 2012

Chronic diseases are the result of a complex interplay between host genetics and the environment. A study conducted by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Cambridge, England analyzed DNA sequencing data from 179 people of African, European, or East Asian origin as part of the 1000 Genomes Pilot Project and discovered that healthy individuals carried an average of 400 mutations in their genes, including around 100 loss-of-function variants that result in the complete inactivation of about 20 genes that encode for proteins. These findings indicate that deleterious mutations, even those that lead to protein damage, do not invariably give rise to disease.

As Professor James Evans from the University of North Carolina, who was not involved in the study, summarized in an NPR health blog:

We’re all mutants. The good news is that most of those mutations do not overtly cause disease, and we appear to have all kinds of redundancy and backup mechanisms to take care of that.

The authors hypothesize that healthy individuals can carry disadvantageous mutations without showing ill effects for a number of possible reasons: an individual may carry just one copy of a gene mutation for a recessive disorder that requires two mutations in order to manifest the disease, the disease may exhibit delayed onset or require additional environmental factors for expression, or the reference catalogs used to identify gene-disease links may be inaccurate. An analysis conducted by the National Center for Genome Resources found that 27 percent of database entries cited in the literature were incorrectly identified.

To account for the discrepancy between genetic predisposition and disease manifestation, in 2005, cancer epidemiologist Dr. Christopher Wild proposed the concept of the exposome, which encompasses “life-course environmental exposures (including lifestyle factors) from the prenatal period onwards” and accounts for factors such as socioeconomic status, chemical contaminants, and gut microflora.

The risk of developing a chronic disease during one’s lifetime may be modeled by G×E: the interaction between a person’s genetics (G) and lifetime exposures (the exposome, E). Identical twin studies reveal that genotype alone cannot determine whether a given phenotype will be expressed, and the interaction between genes and the environment needs to be taken into account.

In fact, the “genes load the gun, environment pulls the trigger” paradigm may be overly simplistic, as Dr. Alessio Fasano at Harvard Medical School has shown that loss of intestinal barrier function is likely also necessary for the development of chronic inflammation, autoimmunity, and cancer.

Two particular gene markers, HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8, are observed in the vast majority of celiac disease cases. While over 30 percent of the U.S. population carries one or both of the necessary genes, only around one percent of Americans have celiac disease.

These data suggest that exposure to gluten through ingestion of wheat, barley, or rye is not sufficient to trigger the development of celiac disease even in individuals with a genetic predisposition. Without the additional loss of intestinal tight junction function, celiac disease is not made manifest. Thus, factors besides genetics are necessary for the development of chronic disease.

Before jumping onto the gene editing bandwagon, we should perhaps investigate the untapped potential in safer treatment methods, such as modifying the diet, restoring mitochondrial function, manipulating the microbiome, and resetting circadian clocks. Attempting to restore normal physiology using more expedient methods prior to making drastic and irreversible genetic changes would serve us well.

Thanks, Nita, for another amazing article. You make complex subjects easy to understand and enjoyable to read, and the amount of research and thought that goes into each article is awesome.

A good summary of some reasons gene therapies (not just gene-editing) may not be the right solutions for all disease. Gene-editing in particular though, could eventually be an incredibly helpful research tool and perhaps even appropriate for ex vivo treatments and other GMO applications!