A few years ago, I heard a TED Talk given by Dr. Shamini Jain and strongly identified with many of the experiences she was describing. Like her, I have seen many scientific paradigms upended during my lifetime, such as the still widely circulated myth that neurogenesis doesn’t occur after childhood or the assumption that lymph nodes don’t exist in the brain.

As was the case for her, my scientific background also initially left me skeptical of complementary and alternative medicine. As I grew older, I tried to make sense of the various approaches espoused by different medicinal camps. Jain’s discussion of the divide between allopathic and alternative medicine got me thinking about how the use of these terms is problematic at a much larger level.

The Appropriation of Ancient Wisdom

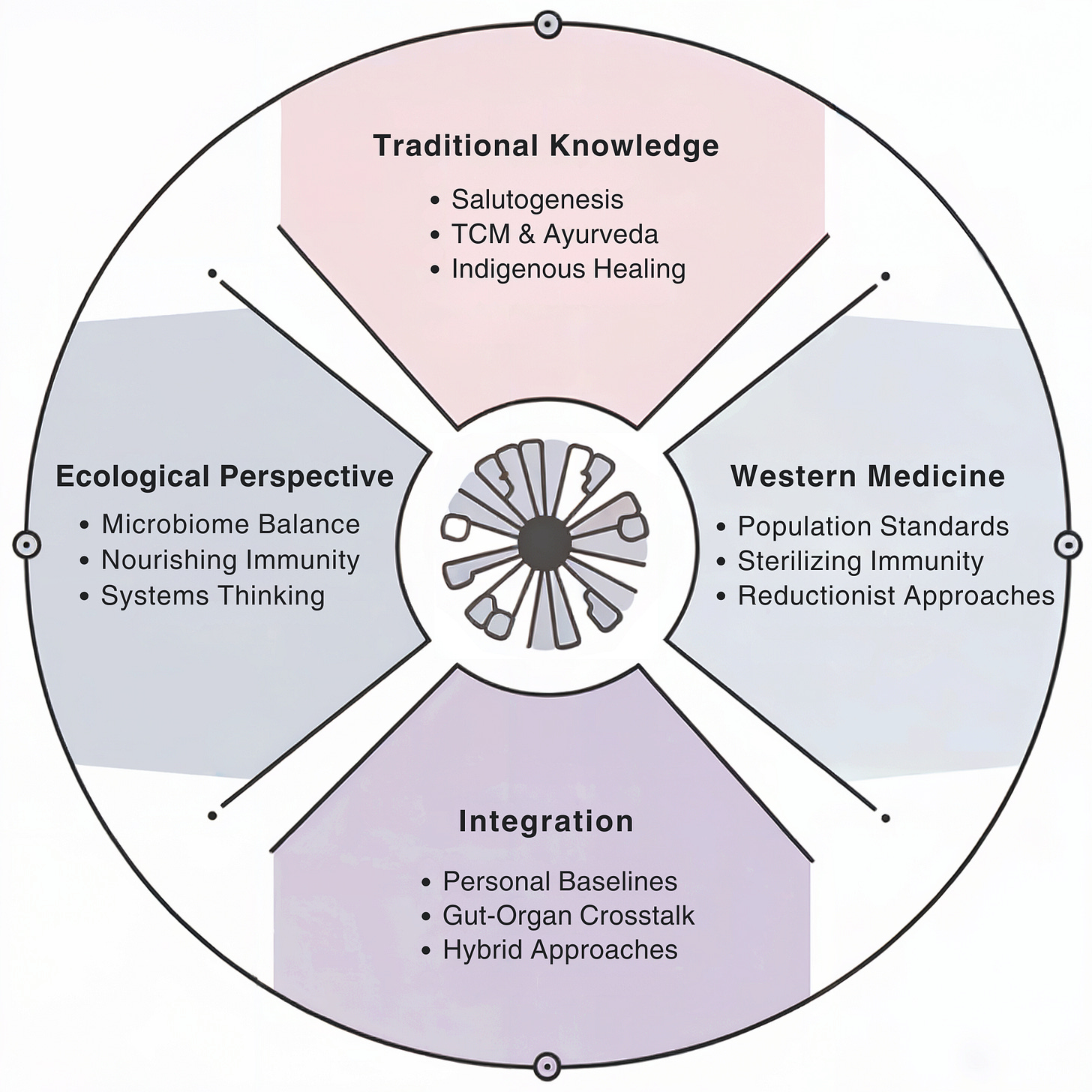

Is progress the consequence of cutting-edge novelty or is it the result of returning to our roots? Is it somewhere in between? Modern medicine prides itself on constant innovation, yet some of its most significant breakthroughs represent rediscovery rather than revolution. What we call progress often represents devolution, or at best, a belated recognition of forgotten knowledge.

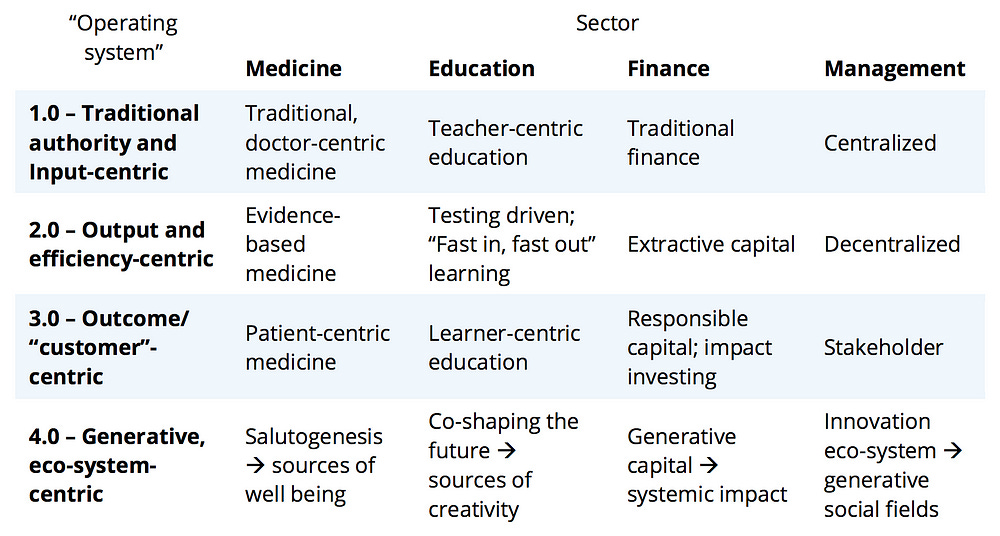

When MIT researcher Otto Scharmer described organizational evolution as a progression of "operating systems," he perpetuated the problematic narrative of a linear timeline whereby the past is inherently less evolved, innovative, and progressive than what lies ahead in the future.

In Scharmer’s estimation, organizations evolve from being authority-driven and input-focused, to prioritizing efficiency and outputs, to emphasizing customer outcomes, and finally to adopting ecosystem-oriented approaches.

This framework is particularly disingenuous in the case of medicine, where salutogenesis, a “4.0 operating system,” actually represents our earliest understanding of health. Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ayurveda, and indigenous healing practices have always exploited natural ingredients to restore wellness.

Yet for centuries, ancient wisdom has been suppressed and systematically appropriated, only gaining legitimacy once discovered and validated by western institutions. When indigenous peoples and marginalized groups are the stewards of knowledge, their practices are dismissed as folklore until repackaged and imbued with profitable meaning by medical institutions and insurance overlords, the self-appointed arbiters of truth.

Even worse, this system of scientific colonialism implies that knowledge from cultures without access to state-of-the-art instruments, such as hunter-gatherer tribes, cannot be validated without encroachment from more “civilized” peoples.

This institutional isolationism perpetuates cycles of suffering by denying patients access to effective treatments that fall outside the dominant medical paradigm. Even if an alternative therapy emerges as a more effective treatment than the prevailing standard of care, a substantial window of time typically elapses before that alternative treatment migrates to default status, if it ever does.

Mind Your Microbes

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) is a procedure that involves transplanting bacteria from the stool of a healthy donor into a patient with a disrupted gut microbiome. The first documented use of FMT was in 4th century China when Ge Hong used a fecal slurry to treat patients with severe food poisoning and diarrhea.

Long considered an experimental therapy, FMT has gradually become part of the standard of care for the treatment of C. difficile colitis. Clostridioides difficile is best characterized as a pathobiont, a microorganism that is usually a part of the host microbiome but can become harmful when the host’s immune status or native microflora are altered.

Antibiotics are a known risk factor for the development of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection (rCDI) because they induce the type of dysbiosis, or microbial imbalance, that allows C. difficile to gain a foothold. By killing both pathogens as well as friendly commensals indiscriminately, antibiotics eliminate the very microbes that keep pathobionts like C. difficile in check.

The evidence supporting FMT's superiority is compelling. A large cohort study involving almost 300 patients demonstrated that FMT outperformed antibiotics when evaluating several different outcomes in patients with rCDI.

These findings were further validated by a 2023 review of six randomized clinical trials (RCTs), which found that FMT not only resolved symptoms better but also resulted in fewer adverse events and overall mortality compared to antibiotic therapy.

But first-line therapy for rCDI still consists of antibiotics while fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT)—despite being safer and more effective— is considered an appropriate course of action only if the patient fails to respond to antibiotics.

Repeated antibiotic treatments for rCDI will lead to more recurrences. Modern medicine has managed to market the cause as the cure. To treat rCDI with antibiotics is to knowingly perpetuate patient suffering. FMT offers a way to break the cycle.

Pathology vs Ecology

Antibiotics and FMT represent two fundamentally different approaches to infectious disease and the practice of medicine more generally: one is an elimination-based approach that seeks to eradicate, and the other is an ecological approach that seeks to restore equilibrium.

Antibiotics aim to annihilate any potentially pathogenic agents, but nature abhors a vacuum. Every single millimeter of your body is colonized, and microbes will always find a way to reclaim the void left behind. FMT at least offers some agency as to which microbes will occupy that niche.

Rather than trying to kill the enemy and select for resistance in the process, FMT addresses the ecological disturbance. Disease is about diplomacy.

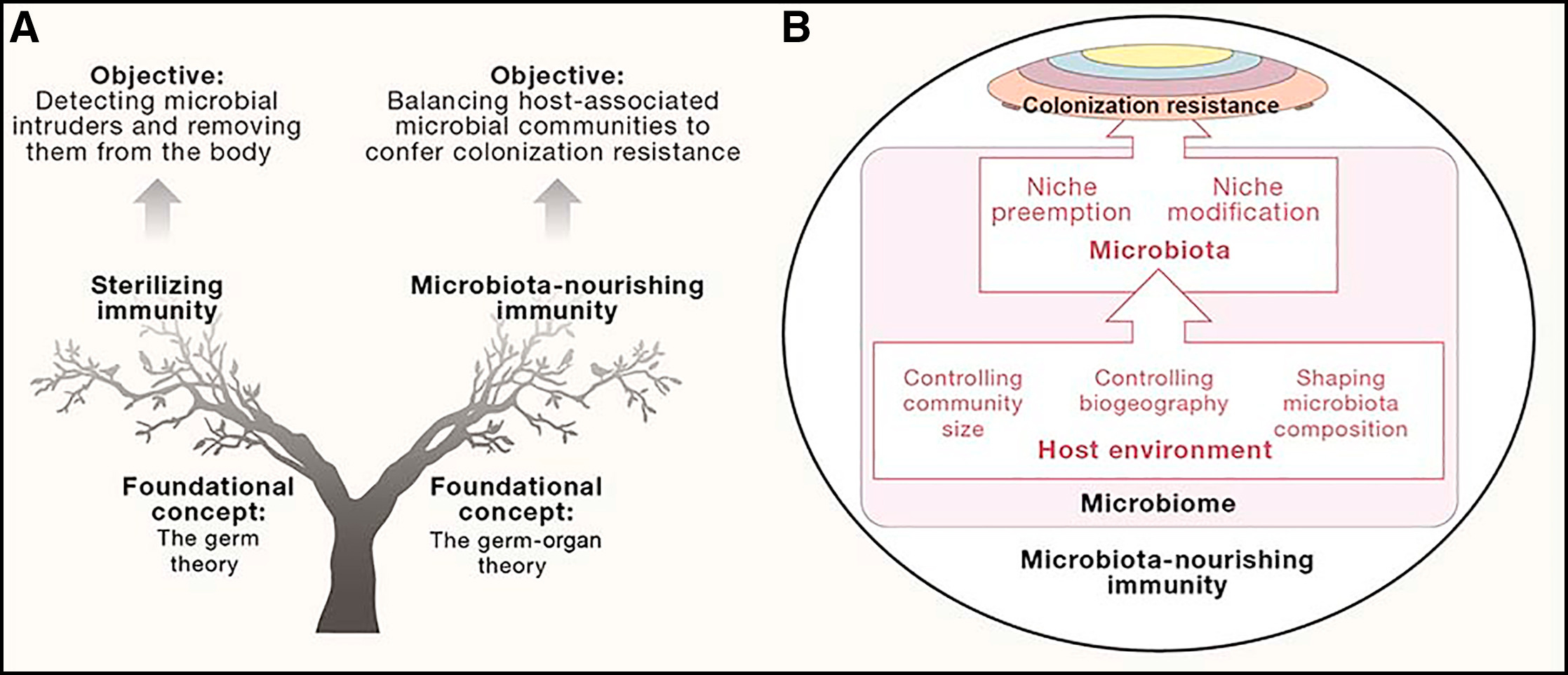

These drastically differing perspectives underlie the discrepancy between sterilizing immunity and microbiota-nourishing immunity. Sterilizing immunity represents our scorched-earth defense system, designed to detect and destroy invaders at all costs. In contrast, microbiota-nourishing immunity operates more like ecological diplomacy, cultivating strategic alliances that guard against threats through collectivism.

The human body balances this duality through mechanisms that support both defensive elimination and ecological restoration. But the vast majority of western medicine, to the detriment of patients, focuses almost exclusively on the former.

Many establishment scientists will be quick to falsely characterize the ecological perspective as an endorsement of the appeal to nature fallacy, a rhetorical technique whereby what is natural is considered good. The ecological perspective focuses on systems dynamics rather than arbitrary delineations of “natural” and “artificial.”

FMT works not because it’s natural but because it restores disrupted microbial ecosystems, as validated by robust clinical outcomes. The case of C. difficile infection treatment exemplifies how modern medicine sometimes perpetuates cycles of intervention that may harm rather than heal.

The preferential use of antibiotics over FMT, despite evidence supporting the latter's superiority, demonstrates our healthcare system's attachment to reductionist approaches over restorative ecological ones. This bias persists even when ecological approaches prove more effective.

These attitudes even pervade approaches to mental health. Whereas western approaches have traditionally sought to avoid and pathologize negative emotions in a frenzied quest for hyperoptimization, eastern perspectives recognize the wisdom of flowing through rather than against our emotional undercurrents.

Like water adapting to its container, this flexibility allows us to observe and move through emotional states without resistance or judgment, an approach western psychology is only now beginning to embrace. It is indeed okay to not be okay.

Personalized vs Population-Based

The chasm between western and eastern perspectives isn’t just philosophical; it manifests in tangible effects on patient outcomes. Western medicine's devotion to standardization, while crucial for reproducibility and large-scale studies, can inadvertently mask clinically significant individual variation.

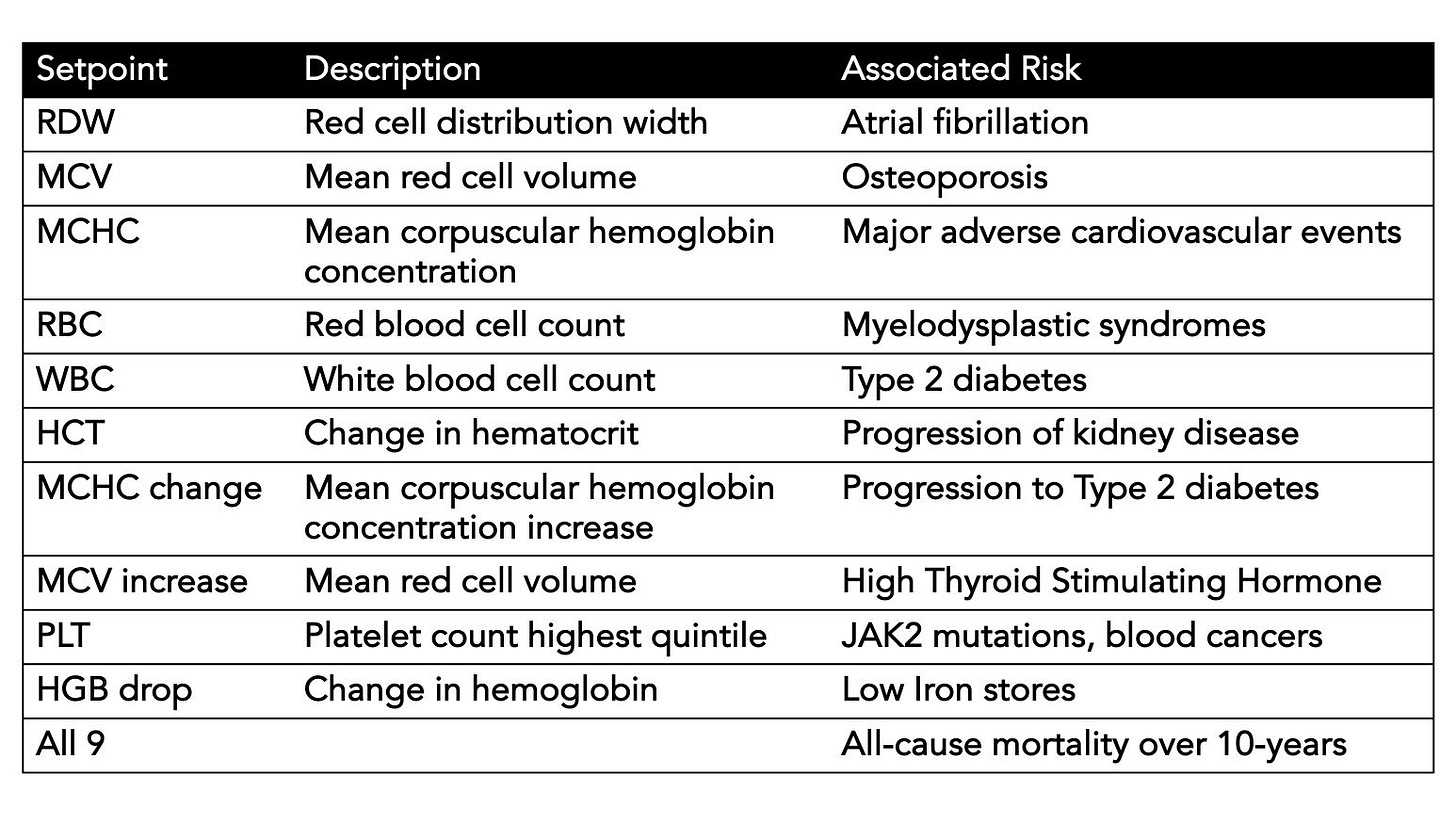

A recent Nature study of over 12,000 patients highlights how our reliance on population-based reference ranges for laboratory tests may obscure meaningful changes at the individual level.

The research examined nine key blood count indices over a 20-year period and found that each person’s metrics remained remarkably stable, and their unique setpoints were as distinctive as a fingerprint or what researchers called an “index of individuality,” differing from 98% of other healthy adults.

Individual setpoints far outperformed population-based references in predicting mortality risk and also revealed unexpected associations with specific diseases—from atrial fibrillation to diabetes to blood cancers—often before traditional diagnostic criteria would raise concerns.

We can’t ignore the potential implications. When we compare a patient's lab values to broad population averages rather than their personal baseline, we risk missing early warning signs of disease or misinterpreting normal individual variation as pathological. Among the 500 million complete blood counts performed annually in the United States alone, how much vital information are we missing by ignoring individual variation?

A drop in hemoglobin that falls within "normal" population ranges might actually signal iron deficiency for a specific patient. A platelet count considered unremarkable by standard measures could indicate nine-fold higher risk of blood cancer-associated mutations when compared to that individual's baseline.

Transforming medicine doesn’t mean abandoning population-based standards but enriching them with individual context. The future of healthcare depends on hybrid systems that can integrate both personal baselines and population insights akin to how gut-immune crosstalk balances both targeted elimination and ecological restoration. Progress lies not in choosing between these perspectives but in building frameworks sophisticated enough to examine multiple levels simultaneously.

Thanks, Nita. Acupuncture, Qi Gong, and meditation have served me well over the decades. Your postings are always a great read.