In this episode of Evolving, I had the opportunity to chat with Richard Sprague, a software engineer, quantified self enthusiast, and co-founder of personal health tracking startups. Sprague discusses the complexities of the microbiome, the limitations of single-point microbiome testing, and the importance of longitudinal sampling.

He shares insights from his extensive self-experimentation data collection, discussing fasting, probiotics, and the impact of alcohol on glucose levels. Sprague also touches on how personal science can empower individuals to optimize their health by tailoring approaches to fit their unique biological responses.

When Big Tech Meets Tiny Microbes

Our bodies contain multitudes. Trillions of microbes live in and on us, forming a complex ecosystem that influences everything from digestion to mood. Understanding this ecosystem presents an exciting frontier for health optimization, one that Richard Sprague has been exploring with the methodical approach of an engineer.

As a former tech executive at Microsoft and Apple, Sprague sees patterns where others might see chaos. He started using personal computers during the early days of the revolution and saw the democratizing potential of technology. This perspective led him to view the body as hardware that could be optimized through the right inputs.

But the microbiome quickly revealed itself as far more complex than any computer system. The body isn't just a machine running code but a dynamic ecosystem constantly responding to countless stimuli.

The Snapshot Fallacy: Why One Test Isn't Enough

One of the most important lessons from Sprague's exploration is that microbiome testing requires multiple samples over time. Our gut bacteria undergo significant shifts even within a 24-hour period, making single-sample testing misleading.

A one-time gut check might capture an unusual day rather than represent an average of your typical microbial makeup. This temporal variance means that meaningful microbiome understanding requires tracking changes over time rather than fixating on a single snapshot. For accurate assessment, longitudinal sampling is essential.

When interpreting microbiome test results, be aware of the "compositional problem." When you take a subset of an environment, you're assuming it's evenly distributed and representative, an assumption that isn't always accurate.

Most microbiome tests report results as percentages (scaled to 100%). This creates a potentially misleading picture where proportion is conflated with abundance. If your test shows 5% Lactobacillus one day and 10% the next, this doesn't mean the bacterial population doubled because the context of the entire ecosystem matters.

The Quantified Gut: Finding Signal in the Noise

Different testing companies use different methods, making direct comparisons tricky. The American Gut project uses filtering techniques that differ from commercial testing services. Even the sampling technique matters. Beneficial bacteria like Akkermansia tend to concentrate near the outer surface of stool where they interact with the intestinal mucosa.

Sprague's advice? If you're tracking your microbiome over time, stick with the same testing laboratory rather than switching between companies. The consistency of methodology matters more than finding the ideal test.

When Sprague interprets microbiome results, he pays special attention to the number of sequencing reads obtained. Low read counts can produce misleading results through undersampling, a bit like trying to understand a forest by looking at just a handful of trees.

N-of-1: Power of Personalized Experimentation

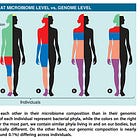

Standard health recommendations often miss the mark because they're based on population averages that may not apply to your unique biology. What works wonderfully for one person might do nothing or even cause problems for another.

This is where self-experimentation becomes valuable. By tracking your responses to specific foods, supplements, or lifestyle changes, you can identify patterns unique to your body. These personalized insights often reveal surprising connections that general studies wouldn’t be able to predict.

Sprague has found that structured tracking reveals counterintuitive findings. Some "healthy" foods might trigger inflammatory responses in certain individuals. Interventions widely considered beneficial might produce unexpected effects given someone's unique physiology.

Geographic Imprints: How Living Abroad Reshaped Sprague’s Microbiome

Your surroundings profoundly influence your microbiome. After living in Japan for a decade, Sprague discovered he had acquired bacteria that could break down polysaccharides in seaweed, microbes typically only found in Japanese populations. This microbial transfer gave him digestive capabilities that most Westerners lack.

The Japanese diet, with its emphasis on fermented foods like miso, natto, and kimchi, supplies beneficial bacteria absent from typical Western diets. These nutritional differences create measurable changes in the microbiome with real health implications.

Cross-cultural studies reveal surprising patterns. Hunter-gatherer populations like the Hadza have drastically different gut bacteria than Western subjects. Notably, they completely lack Bifidobacterium, a genus many probiotic companies tout as essential to good health. These variations across global populations challenge our assumptions about what a "healthy microbiome” should contain.

Microbial Redesign: Diet and Fasting as Tools

The microbiome responds rapidly to dietary changes. Fasting causes shifts that reduce food-dependent bacteria while allowing hardier species to flourish. This microbial reset triggers broader effects including cellular cleanup processes and metabolic changes.

Antibiotics represent powerful but blunt tools for altering the microbiome. Their action affects beneficial microbes alongside harmful ones, often with lasting consequences. After antibiotics, your microbiome may establish a new baseline that is significantly different from the one you had before.

Different foods selectively feed certain bacterial species. Fibers preferentially nourish specific butyrate-producing bacteria while fermented foods introduce transient microbes that, even without permanent colonization, can positively influence immune function during their passage through your system.

Gut-Brain Axis & Glymphatic System

Our understanding of body systems constantly evolves. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, a principle perfectly illustrated by the discovery of the glymphatic system, the immune component that exists in the brain, in 2015. Because scientists were previously unable to visualize lymph nodes in the brain, they assumed they simply didn’t exist.

This discovery has profound implications for how we think about brain health. Some researchers suspect connections between the microbiome and neurodegenerative conditions. For instance, loss of smell is an early symptom of Alzheimer's disease, which could indicate disruptions in the nasal microbiome.

These findings remind us to approach the microbiome with humility. As Sprague emphasizes, our health emerges from complex networks involving microbes, genes, diet, and environment — not isolated components operating independently.

Data-Driven Discoveries: Personal Health Tracking Reveals Hidden Patterns

Modern technology lets us measure what was previously invisible. Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) gives you a readout of how your body responds to specific foods, enabling personalized dietary choices beyond generic recommendations.

When combined with microbiome data, these measurements reveal connections between gut bacteria and whole-body responses. Patterns emerge showing how specific microbes influence everything from inflammation markers to mood regulation. This transforms vague notions about listening to your body into precise, measurable feedback.

The most valuable insights come from thoughtful self-experimentation. By systematically varying inputs while measuring outcomes, you can uncover cause-and-effect relationships unique to your biology. Sprague discovered that, contrary to expectations, alcohol actually lowered his blood glucose levels.

Technology for Better Health & Productivity with Avisha NessAiver of Distilled Science

In a world where simplicity is attractive, Avisha NessAiver, founder of Distilled Science, bucks trends and embraces nuance while setting out to maximize his health, income, & productivity.

Connect with Richard Sprague

If you'd like help interpreting your microbiome results or gaining deeper health insights, Sprague welcomes your questions. You can follow his work through Twitter, his Substack newsletter below, or his personal website where he shares ongoing experiments and invites others to engage with him.

Share this post